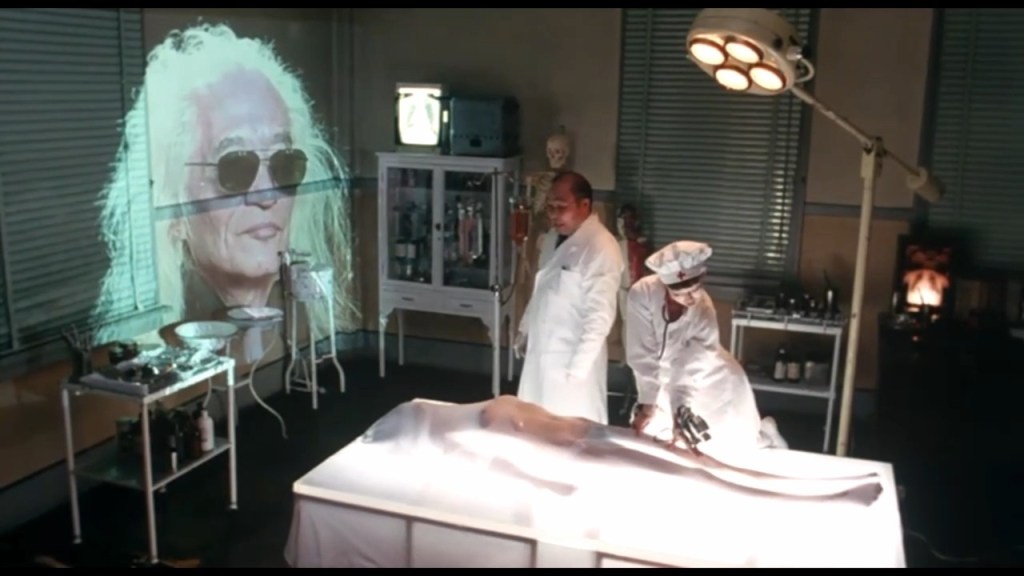

A surrealist theatrical artifact of cinematic proportions whose meta-narrative presupposes—following the appearance of old Omiya at the beach session—human reincarnation as the key to understanding the dizzying comings and goings of photographer Ishida, from his present as a photographer to his past as a captain with the sexy Sada Abe. It also recovers details of the legendary crime of 1936, after poetically evoking the fateful tragic ending between the former prostitute and her lover, which culminates in her cutting off his genitals ‘because it’s mine, no one else can lick his cock,’ as she repeats at the trial. While the photographer has these visions of his past life, led by the old man, newspaper clippings from that time with a variety of opinions are simultaneously interspersed.

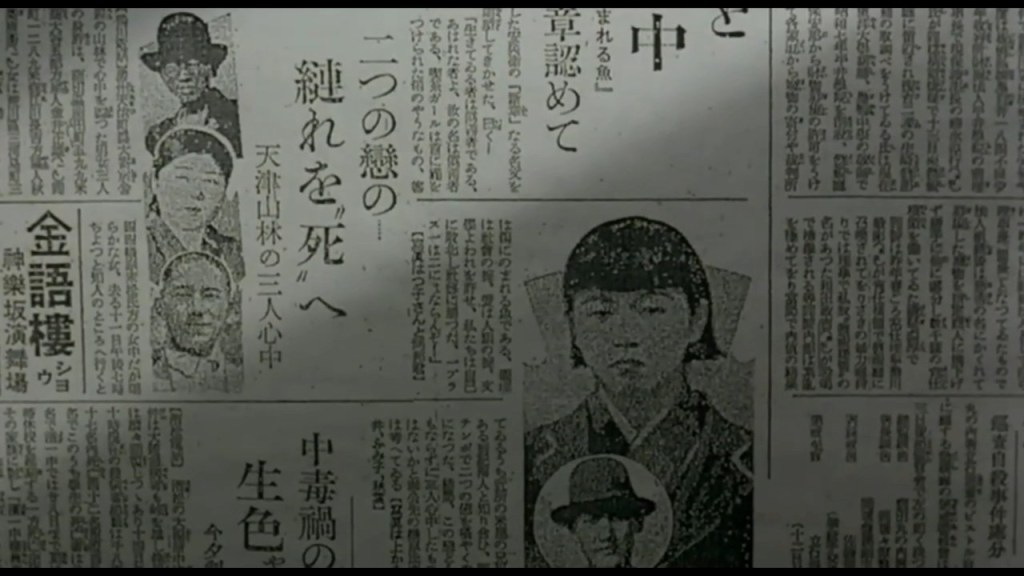

One of them portrays events that echo the scandal caused by Sada’s crime: ‘Martyrdom of young men and women.’ Or the headline that reads ‘Accused of murder and prostitution.’ This highlights that the woman shows no fear of the death penalty and appears in court wearing the bloodstained clothes she wore at the time of the crime. This example, interspersed throughout the film via facsimiles, first shows the significant impact on the judge due to the defendant’s defiant attitude, but also, other journalistic bullet points such as ‘Foreign student encounters difficulties in Mihara-yama’ allow us to understand that the film does not only narrate Sada’s obsession and crime, but also how the era was marked by other cases that fed the collective imagination of a drifting youth, ready for self-destruction. I took the liberty of digressing because Sada stated that her intention was to commit suicide on Mount Mihara, whose volcano is emblematic of the island of Izu Oshima at the time, known in the 1930s and 1940s as a tragic symbol because hundreds of people travelled there to commit suicide, a phenomenon widely covered by the press at the time.

The reference to ‘Mihara Mountain’ in the headline is not accidental; it directly conveys the symbolism of despair, tragedy and romantic death that was so prevalent at the time. Omiya Goro, as I said, the symbolic character who appears to the photographer on the beach, is, I understand, ‘symbolic’ rather than real-intratextual, not only because we will eventually see that he is hermaphroditic or at least has changed sex… but also because of his omniscience regarding the story as he reviews the events with Ishida. For example, he tells the photographer from his first tour, ‘Accumulated deeds and karma will never disappear, even within the limits of time and space.’

But Omiya is not a simple Socratic daimon, you know, like the one Plato’s teacher referred to, and whom he consulted within himself for his moral intellectualism; he is one for all the characters, compare their arguments towards Sada. They stand in front of the large table, and it is understood that the old man embraces the vibe or human essence that makes it possible to continue loving despite the centuries.

In front of the banquet, which I repeat, I understand to be a previous allegory of the same court with which the film closes and the prostitute is judged, Omiya tells her to eat. Sada replies, ‘As long as I can eat, sleep, and have the man I love put his cock inside me, I will be satisfied.’ Unmoved, Omiya replies, ‘Sada, the present is fleeting. Don’t spit on the leaves. Do you have dignity, pride, or intelligence as a human being?’ In addition to being based on the work of Shigenori Takechi, the film should be seen as an artistic exploration and, as I indicated, the pretext of reincarnation provides the meta-discourse through the different ‘persons’ who must have corresponded to Ishida, a photographer in real time having an affair with Sada, the wife of an enigmatic old man. There, the sequences when he was captain and so on are interwoven to suggest that love, if it appeals to the artistic, transcends time and space, even if the end is grim, with strangulation and castration.

Leave a comment