We should applaud the departure from the usual yakuza trope, that profile of the thug in the 1960s and 1970s, who had already chosen stability, or settled down with some business, and an injustice to himself or a loved one incites his revenge, which occurs in a bloody denouement.The downside is that breaking this paradigm seemed to lead to something similar or worse, surpassing the past by decades: the hitman disturbed in his childhood who is now a killing machine. Fortunately, this was not the case, because the story was not about Kenji’s childhood traumas.

The performances are convincing, but the direction is lacking. Take, for example, the remarkable execution of the crime sequence in Kitashinji—a travelling shot with a handheld camera from the moment the yakuza arrives at the club—in contrast to the artificial scene of Kenji receiving a complaint from the woman he spent the night with in the luxury loft, which felt out of place.

In other words, while there are sequences where Ishihara could have used some professional advice on which shots to omit or repeat and which ones to leave in the film, there are other very interesting – not to say intelligent – ones, such as the one where the incompetent yakuza Atsuhi (Kenji’s childhood friend) is sent with two companions by the leader of the Otani clan, Rikiya, to confront the wayward Tay Leon, where there is an explicit ellipsis when the trio stabs the guy while holding him down.

They are three childhood friends from the streets, the girl Kanako, Atsushi and Kenji, who was always silent and had a scarred face. They played and had fun until they escorted Kenji home, where a despicable adult was waiting for him, who mistreated him and sold him to the yakuza for 800,000 yen.

This part of the film takes up almost half an hour, but it’s worth it, as I said, to force unsuspecting viewers like me to assume that it will be about revenge on the world for Kenji, since we don’t know the fate of the other two children until this second stage of the film, when they have three daughters and are married and living more or less stable lives, albeit with a little family friction. Kenji, on the other hand, is a hitman in Kansai Fukumoto. After making a mistake in the Kitashinji crime, the two clans (Kansai and Otani) meet to apologise and promise to pay 240 million yen for the incident.

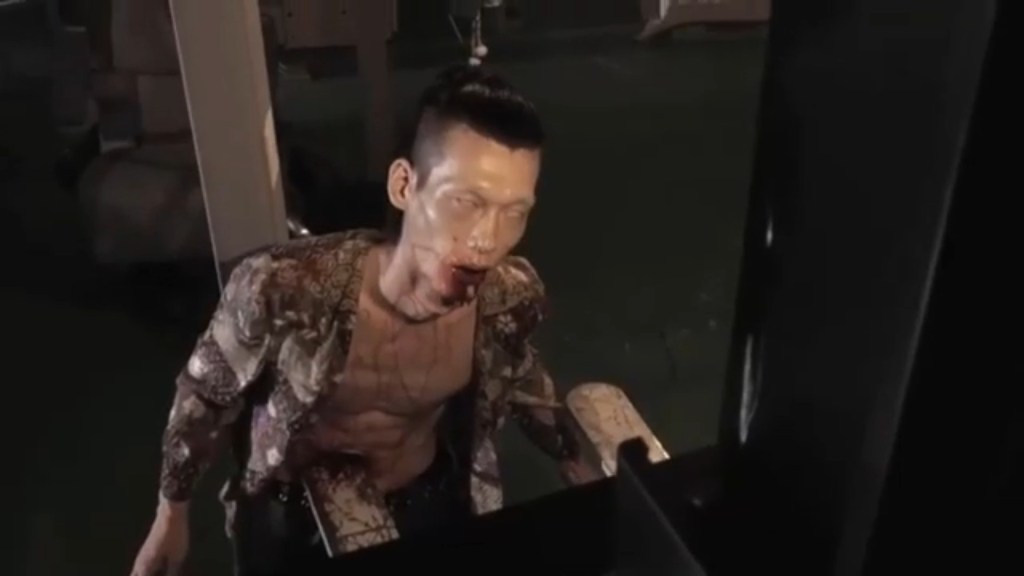

When the deadline arrives, the Kansai group brings the money and then offers a toast, after which they murder their rivals. In the midst of the hurricane, Atsushi, who is still a considerate and kind man, is sent, as I said, to appease the fierce and mute Tay Leon. Fortunately for Atsushi, Kenji finds him and ends up killing Tay, albeit with difficulty, and hands the money to Atsushi, who, upon arriving home, has forgotten his anniversary party but announces to Kanako that he is changing jobs.

Frightened, she asks him if he has stolen from someone, and Atsushi tells her that the company went bankrupt. Given that the plot leads the viewer to see the man who beats up many people as masculine and those who prefer to use their fists and don’t know how to fight as losers, through the character of Atsushi, the film asks his wife why she stays with him. The answer is serpentine and takes us back to the last minute of the film, to their childhood, when they were children and after finding a snake on the path, Kanako tries to step on it shouting ‘die’, but Atsushi tells her that it is a living being and takes her friend away. Later, she confesses that her fondness for him is because of his inherent kindness.

Leave a comment