“The monstrous thing is not that men have created roses out of this dung heap, but that, for some reason or other, they should want roses”, I remember Miller and excrement, now that these characters have achieved material miracle and stable marriage. It is true that the lack of communication, similar to that conveyed by Antonioni, is taken to the point of disillusionment with false success, which will populate the openly existential plot of this work, photographed with guts and discreet but evident majesty. Sometimes one feels like entering into this kind of phlegmatic trance; lacerating oneself with the futility of life’s great desires once they have been fulfilled.

Watch trailer https://aqueronte72.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/trai.mp4

Stories – like that of Luis and his family – with which the viewer breathes ‘a kind of sadness’, thanks to the characters who exude a kind of sadness in their perfect, or at least comfortable and prosperous bourgeois life. Any kind of higher meaning or great significance that holds human cohesion together like glue without the arbitrary, always arbitrary will, as Schopenhauer has taught us so well, is absent, and I fear not only for the characters. If the mood of the characters here is like Antonioni’s, reinforced by a sublime melodic score (I have already pointed out elsewhere how unfairly underrated it is) by the maestro Erlon Chaves, the narrative rhythm, although in the form of noir, is undoubtedly inherited from the cinema of Resnais.

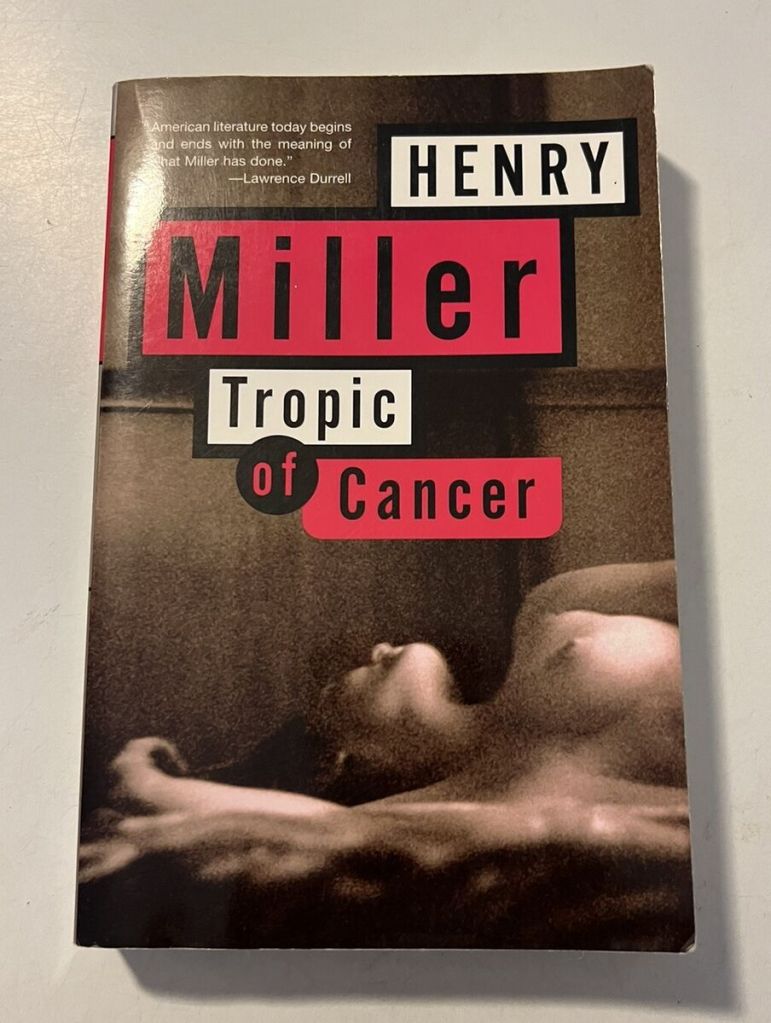

So, it seems that each person has the last word, giving themselves volitional momentum towards their life goals, even though Camus glimpsed the absence of a real rational thread in the brand-new model family life, especially since the post-war period with the welfare state and other promises. Henry Miller, my favourite vagabond, addresses in chapter 8 of his ‘Tropic of Cancer’ a histrionic metaphor of shit as something real, beyond the hopes that anyone may have in their projects or existential goals, however genuine they may be.

And let it be noted that I am quoting a philosopher of letters who lived under bridges and, when using public toilets, rationalised urinals. In chapter 8, the narrator of the novel, Miller’s alter ego, is a former American expatriate in Paris who recalls taking a Hindu visitor on a tour of the city. Since his arrival in the City of Lights, the Indian had talked to him about Gandhi and the salvation of man through non-violence, abstinence and spiritual visions influenced by ideas of purity and miracles. The narrator, Miller, laughs respectfully but at one point takes Nanantatee to a brothel. Nanantatee, absolutely nervous and inexperienced, becomes confused during his encounter with the prostitutes when he tells the narrator that he wants to go to the toilet, but in reality he is hiding the fact that he needs to defecate.

Miller asks him to use the bidet (the Western device for genital hygiene), but the Hindu misinterprets the advice and defecates inside the bidet instead of rinsing himself or urinating. The prostitutes and even the owner are alarmed by the two huge faeces, and the humiliating yet comical episode ends up triggering Miller’s usual existential philosophy based on scatology. Human absurdity is thus revealed: men create ‘roses’ from a ‘pile of manure’ (chaotic life), but what is monstrous is that they want roses, longing for illusory miracles such as the Eucharist, when reality is as crude as the Hindu’s two excrements. Of course, the miracle Miller refers to is that of the Eucharist, bread and wine, but he relates it to the terminal (eschatological) nature of shit, and so this reviewer likens the film to the miracle of glory or the happiness of a man who prefers to fulfil his dream of building his house rather than going to Europe, for example. The beautiful woman with the perfect body, the well-built husband, albeit middle-aged and with sufficient financial resources, the healthy children and the dream house on the beach. Should anything be missing?

To start with, Luis knows from the outset that the perpetrator of the crime, the woman who was run over, was his wife Maria Clara (his mother already knows, he says to himself when his two children go to call the police). But in addition, as we shall see, Luis falls into the existential trap of the good family and the supposedly superior achievement of having built his home. For what? First comes boredom, then that damn air that Maria Clara never stops complaining about, this or that. To be unhappy and still commit infidelity with Dréia, he sought something higher, a post-rock façade, marriage, union, affection. Discovered in his infidelity, divorce follows, and of course his wife is discovered with an impenetrable zoom of moral ambiguity.

Leave a comment