The first great thing about this film is that it goes unnoticed despite highlighting the simplicity and uniqueness of a moral and hard-working hero like Yoshida Isokichi, who never even dreamed of becoming the patriarchal authority of the coal miners and dockworkers at the steel mill in Wakamatsu.But earning money from gambling—and avoiding fights with bad losers—to help Tenzo buy his own boat not only earned him the nickname An-chan (brother) from workers like Seikichi Hanayama, but also the nickname daishiru when he decided to leave the comfort of his home and work on the docks of Kyushu. Makino transcends the ninkyō eiga genre and turns what could have been a biographical fragment or docudrama about the local boss and later public official who championed labour rights in more than one arena into something else.

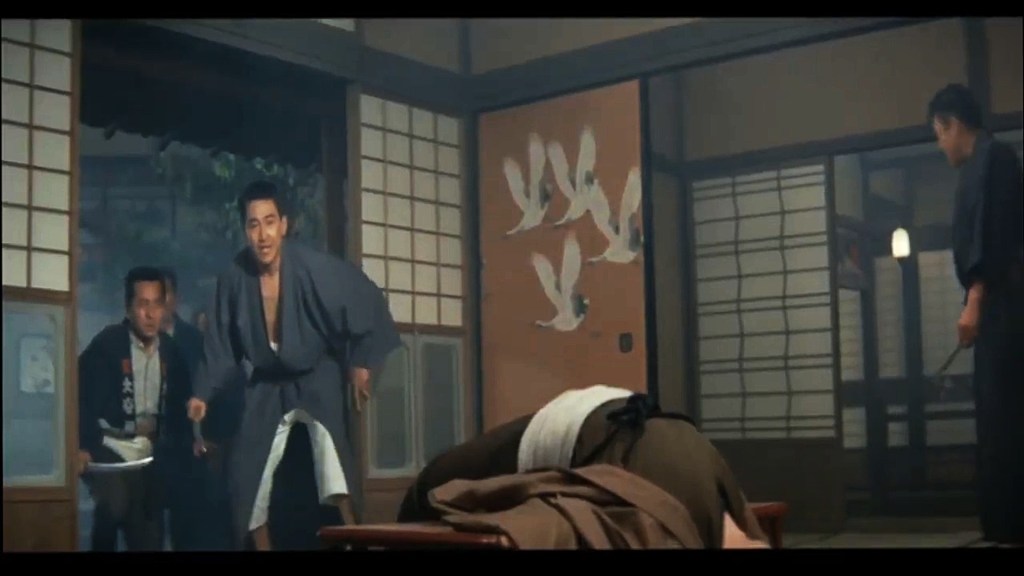

The notoriety Yoshida gained as the boss of the dockworkers, whom he supported as much as he could, was cemented when he intervened unexpectedly in a dispute between the head of the Tobata clan and the crooked Iwaman, who was interested in and master of corruption. In the final scenes of violence in the port, a man was killed and Yoshida asked Tobata to accept his word that he, Yoshida, would take responsibility, promising to pay 1,000 ryu the next day because, according to Otaki’s henchman, that was the stratospheric sum it was worth.

As the deadline was about to expire, the beautiful Oryu, an intrepid geisha who had backed him up in a violent scene at the beginning, when Yoshida was being pursued by men from another clan to settle scores, pulled out a gun and held the mob inside the gambling den.

She, who had sworn to love him forever, lent him the money she had saved from her work and promised that once he, Yoshida, and Wakamatsu were saved, she would wait for the hero for as long as necessary while he left for his political duties. Yoshida, who had his origins in the underworld but was clearly reformed or absolved by himself, now put giri, or the public interest, before his ninjō, or personal interest. Unfortunately, when he returned during the Meiji 31 period, his sister fell ill and made Isokichi promise that, in order to save the Yoshida family, he would marry Ofuji, a young woman without parents who had been living with them for a long time.

This broke his promise to Oryu, and she, drunk on sake, could not forgive him for what she considered betrayal, especially since she had waited for him. During those turbulent days, many violent excesses occurred in the establishments there, and Iwaman and his henchmen took advantage of this to summon the chambers of commerce and found an illegal shock group, hiring vagrants to defend the local businesses. Yoshida opposed this because he was not supported by the other residents, who were not taken into account. Meanwhile, a hitman was sent to assassinate him, but after drinking sake, he was unable to kill him, perhaps because he was already ill. The hitman ended up in hospital and Yoshida won him over by caring for him, in short, giving him another chance. The clashes between groups of workers from both clans continued, and the consul or deputy Yanagawa arrived in the village to settle the disputes, but in reality he agreed with Iwamaki and was immediately expelled from the meeting, given a time limit to leave the place. It wasn’t long before Yoshida ran into Oryu on the street, who immediately mocked him cruelly because she was the one behind Yanagawa’s impositions.

‘Now it’s your turn to leave, just as I suffered when you left and came back to marry another woman.’ Oryu soon realised that she had made a mistake because now she would not be able to see him, not even there. In any case, Yoshida said he would not leave and organised an assault on Iwamaki’s quarters. As always, the end was bloody, and Oryu did not live to see the outcome. The story is sad and painful.

Leave a comment