A unique example of yakuza chivalry. Makino lays the foundations for a series of films whose moral epicentre revolves around the labour and economic contradictions—increasingly latent in Meiji-era Japan—between the stagnant feudal tradition and the winds of modern industrialisation. At first glance, it is a simple plot: the Okiyama group’s unfair competition against Kibamasa escalates until crime becomes normalised, thus justifying the tragic, almost operatic finale. However, this breaks with the openly Manichean fiction paradigm of the 1950s, where yakuza bandits are noble, pacifist and there can be no hint of evil in their causes or their actions; think, for example, of the romanticisation of the Jirochô sangokushi saga: (1952), Jirochô Shimizu (1954) or that of his one-eyed lieutenant Ishimatsu – Man from Shimizu (1958).

With this film, however, Makino inaugurates a fascinating neo-realist vision – if I may use the crude expression – whose highly complex analysis is obviously more raw but ad hoc to the flesh-and-blood characters who have nourished many of the legends on the subject for a century and a half; Here, honour and fair competition between the Kibamasa clan clash with murders committed from behind, such as that perpetrated on the jovial and somewhat womanising Tetsuji, or the cowardly arson attacks carried out by surprise as retaliation, more typical of guerrilla warfare than of a confrontation with war cries, ceasefire flags and the respective codes of war.

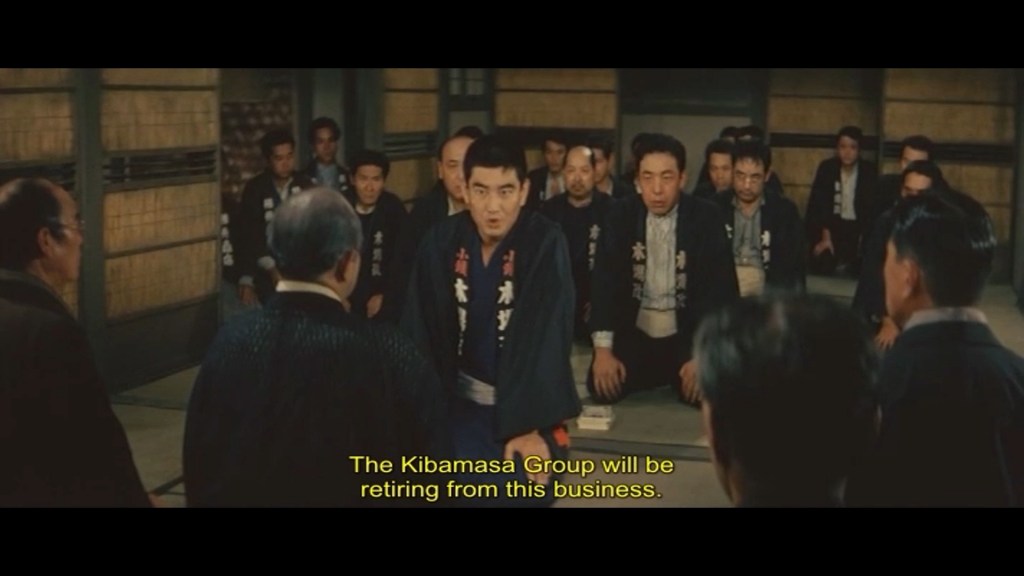

Another detail of this extraordinary film, and why I referred to it as a ‘complex narrative,’ is the multiplicity of conflicting egos: the man who takes Kibamasa’s place, Chokichi (Takakura), is a former soldier, while his comrades on the same side want to avenge their deceased leader immediately, as a guild, with a logic more akin to union revenge, which ipso facto leads to a strike due to the huge number of customers they are losing. And yet another perspective can be perceived within Kibamasa, that of Seiji (Nakamura). I said flesh and blood. Chokichi does not appoint himself leader, he is elected and acknowledges, ‘I have no experience in business.

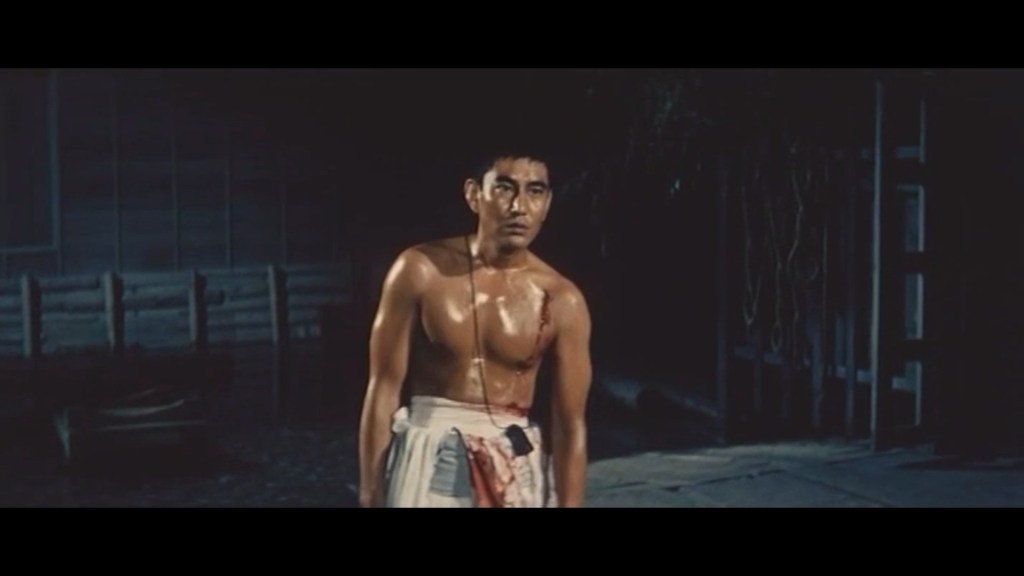

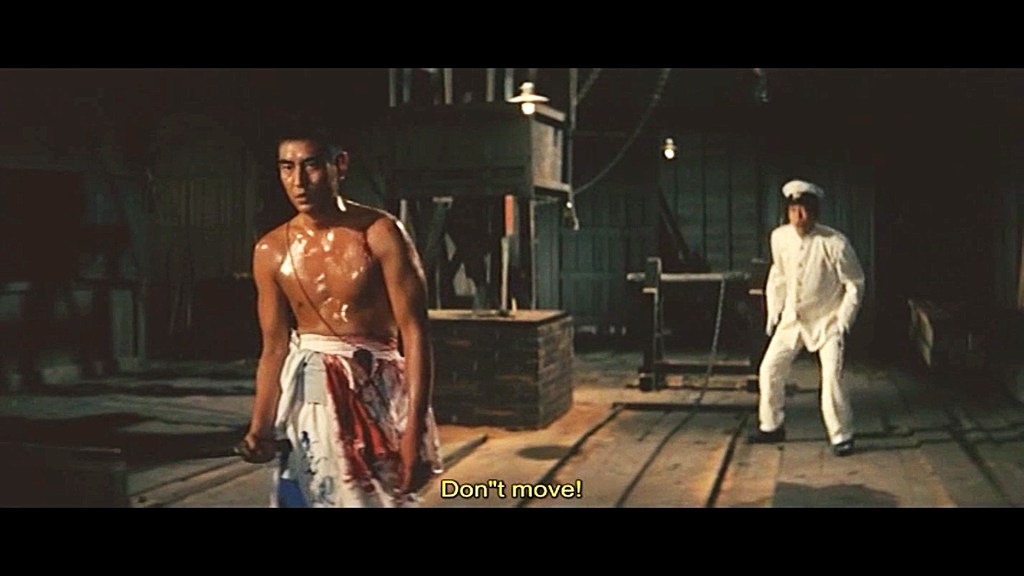

Seiji, please educate me,’ to which Seiji replies, ‘Well, I’m just a gambler, I don’t know how to live in the light of day’ (0:23:19). Note also, on the one hand, the ritualised duels with swords and knives in Seiji’s act of suicide, more similar to that of a samurai, or even a kamikaze in war, than that of a yakuza who only snatches – in contrast to the use of firearms by the Okiyama clan’s henchmen to eliminate him without much ado or shame for the times gone by, or for their opponent with a katana. And speaking of times that are passing, from the beginning, the hostility that arises between the two gangs over this ‘Domain,’ the area for transporting cargo and timber, is obvious, not only because of the competition for the Kiba territory to the detriment of the Kibamasa group, who had controlled that territory for decades, but also because of the disloyalty to traditional values that I have referred to.

For example, take the leader Okiyama Nisiburo, who mocks the elderly leader of the rival group before he dies, saying, ‘It’s sad to see how you’ve aged,’ he says disrespectfully, and as if that were not enough, he has bought the support of the local police authorities to intimidate customers who were already refusing to continue using Okiyama’s freight transport service because he had increased the fare by a high percentage. Then suddenly, the authorities burst in with a show of force and addressed the timber customers: ‘Who cares about your stupid profits as merchants? Transport the timber today or you will be prosecuted.’ Kibamasa’s group recovered some customers who urgently needed to transport their goods and, even without enough staff, took the risk of moving everything and meeting the authorities’ deadline. In other words, the script is written to show that it is not the good guys who win, even if they are kind and follow the rules (this is not a Netflix or Walt Disney film). Proof of this is that in order to load and assemble all the wood and other materials, they had to face Okiyama’s men, who arrived in the middle of the night looking for trouble, interrupting the operation and sabotaging Kibamasa.

They succeed thanks to one of Kibamasa’s men, the loyal Tsurumatsu, who distracts the rowdy men at the cost of being beaten almost to death. But it was all in vain, because soon after, a devastating fire breaks out, ruining Kibamasa. The outcome, therefore, should be seen as director Makino’s subtext; he emphasises with the final tragedy that in a world without rules, and without an authority to enforce those that have worked and existed, the side that maintained competition with honour ultimately chooses crime. It chooses the same game as its rivals, pursuing each one to kill them and thus, even in this way, unfortunately, not only Okiyama’s side perishes, but also the members of Kibamasa except Chokichi. However, the last image that the disappointed audience will see is the tabloid with the photo of the former military man and former leader of the Kibamasa group behind bars, serving time as the person responsible for the murders.

Leave a comment