Despite its use of humour, the film is not only discouraging but also nightmarish, because neither Taiyo manages to save himself nor do the workers defend their dignity at work, at least not successfully, despite their heroic resistance. But this is the most terrifying thing: Kajima’s criticism here, which must have seemed exaggerated and even dystopian in 1994, predicts a decade in advance the same stupid neoliberal measures used by Enron, which started out as a natural gas company but, inventing warm water, came up with a restructuring plan to save its finances, and thus, the Metropolitan Special Sales Division created in this film seems to have been copied by the geniuses at Enron in their Special Purpose Entities, designed to sweep all the trash and mess of liabilities under the rug and hide fundamental financial problems.

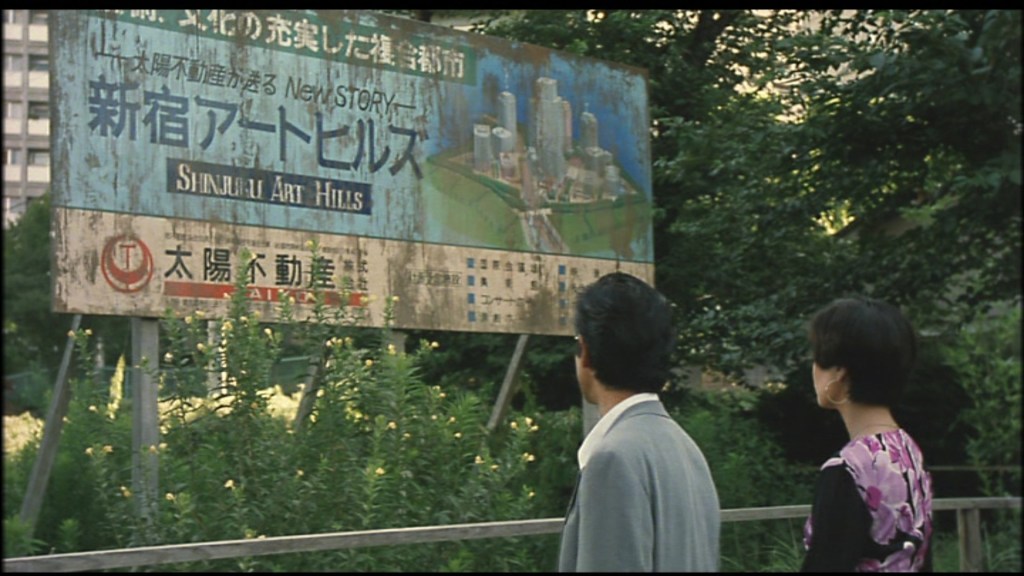

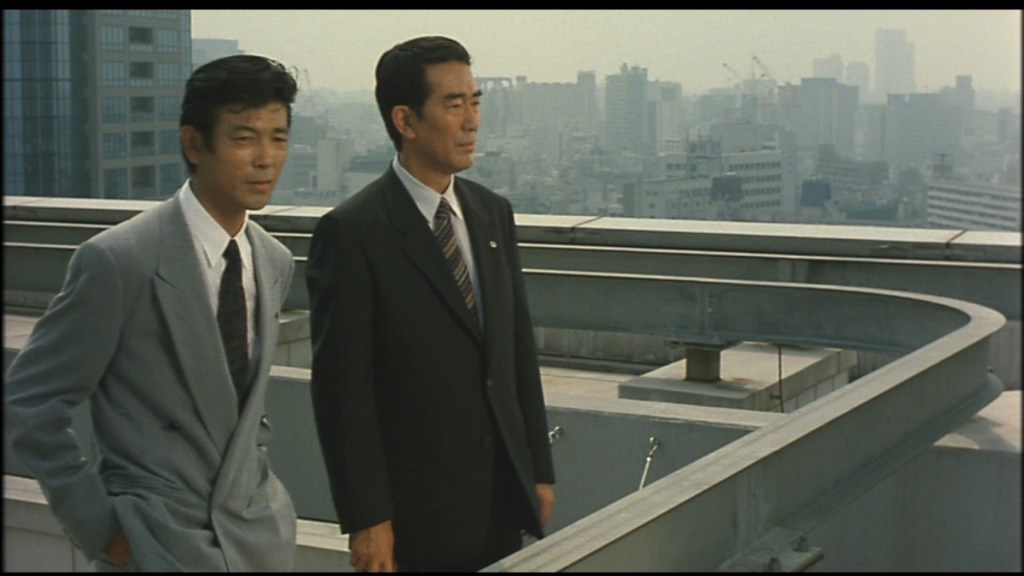

“Shudan-sasen turns out to be an extraordinarily visionary work that anticipated with disturbing accuracy the dynamics of corporate capitalism that we later saw materialise in cases such as Enron. It must not have been easy to accept Hisashi Nozawa’s script. In addition to the enthusiasm of the Japanese economic bubble of the 1980s, this dystopia – I insist on seeing it as such at the time it was released – shows hypocrisy, hypocrisy, corporate and labour hypocrisy from beginning to end, and exposes a disloyal corporation that consumes its workers by demanding unattainable goals under threat of dismissal, like rubbish in a Japan that traditionally guaranteed lifetime employment, i.e. loyalty. The film begins by putting into perspective how, due to the real estate bubble, Taiyo Real Estate suffered a debt of 120 billion yen and now has a portfolio of properties acquired during the real estate bubble that is worth less than a third of their original value. To this end, it has hired the blunt consultant Takasugi. This scene at the beginning is key because it sets out the restructuring plan to be followed—unachievable, as I said—forcing him to betray his own principles. Observe Takasugi in front of the senior executives at the long conference table, note how he says, ‘I am here to help rebuild your company, not to fire people,’ and in the same scene adds his proposal for mass layoffs, ‘to reduce personnel costs by 3 billion yen in a three-year plan.’ Wow, I’m not here to fire you, but I’m here to fire you.

Hypocrisy reigns supreme and is inherent in corporate restructuring speeches. If what they were looking for was to lay off the most vulnerable, then the creation of the Metropolitan Special Sales Division, whose supposed objective is to ‘reduce the stock of dead real estate in residential and office buildings,’ with an ambitious sales plan of 1.5 billion yen, and the appointment of Hiroshi Shinoda as head of the division, seems like a corporate joke. The film shows the different stages of the slow-burning fraud, for example with sabotage and external pressure. The situation is complicated when an arson attack is carried out in Atsugi Towns by Kohei Hanzawa, the department’s second sales manager. In the end, the department fails to achieve its target, obtaining only 720 million yen of the 1.5 billion required. For this reason, in another of the film’s key scenes, one of the members of the new work team explodes and says When the character says, ‘We should all carry the mikoshi, but you’re the one carrying it,’ he is denouncing how collective work falls disproportionately on certain individuals while others benefit without contributing equitably, alluding to the portable altar used in traditional Japanese festivals known as matsuri, which, incidentally, is carried on the shoulders of groups of people working together to transport it in procession. In this context, the phrase symbolises the idea that everyone should share the burden of adversity and work as a team, as is done when carrying a mikoshi during a festival.

It is a call for solidarity, mutual support and the importance of facing challenges together, rather than just a few bearing the burden. Meanwhile, we see high-powered CEOs romancing their secretaries and even sexually abusing them, without the slightest concern for the imminent waste of human capital. The bitter metaphor is clear: the responsibility for saving Taiyo falls solely on the most vulnerable layer of the company, just as it did at Enron until its bankruptcy. Essentially, this is the key to this work, which highlights the dehumanisation and the hollow and abusive rhetoric used to blame the workforce for losses that were unsustainable from the outset. How right the child was to look at the charred rat at the beginning, the rat used by the Yakuza to provoke their misdeeds, and the child, staring into infinity, wonders, ‘Who decides who gets to live and who must be sacrificed?’

Leave a comment