At 70, Fresnay has more aura and injects more energy into the story than Trintignant and Barbara Lass combined, even though they are in the prime of their youth. I will return to this subtext of the plot. For now, it must be said that it is wonderful how a conceited and stupid architect like Desvignes, and a bunch of modern, or let’s call them entrepreneurial, or let’s call them futuristic real estate visionaries, try to blackmail old Captain Valliant into selling his property, infecting him with a sense of urgency and a civilisational backwardness for which Fresnay’s character is in no way responsible. In fact, the president of the real estate company allows him to win the lawsuit or dispute over not leaving the place, but only to increase the price and gain interest to the detriment of the other tenants.

Armand Vallin suddenly stops progress! Wow! The transparent narcissism and stupidity of the architect Desvignes is unmatched, which is perhaps why Ania has set her sights on him. Ania is a student who has just arrived from Poland and was looking for a cheap room to stay in, and the old man almost fired her, but he thought better of it. The romance that spontaneously blossoms between the architect and Ania is intended to breathe romance into the plot. It doesn’t work because Trintignant’s performance is terrible in terms of romantic expressiveness. In any case, the scene with the two of them on either side of the train platforms is beautiful and serves its purpose.

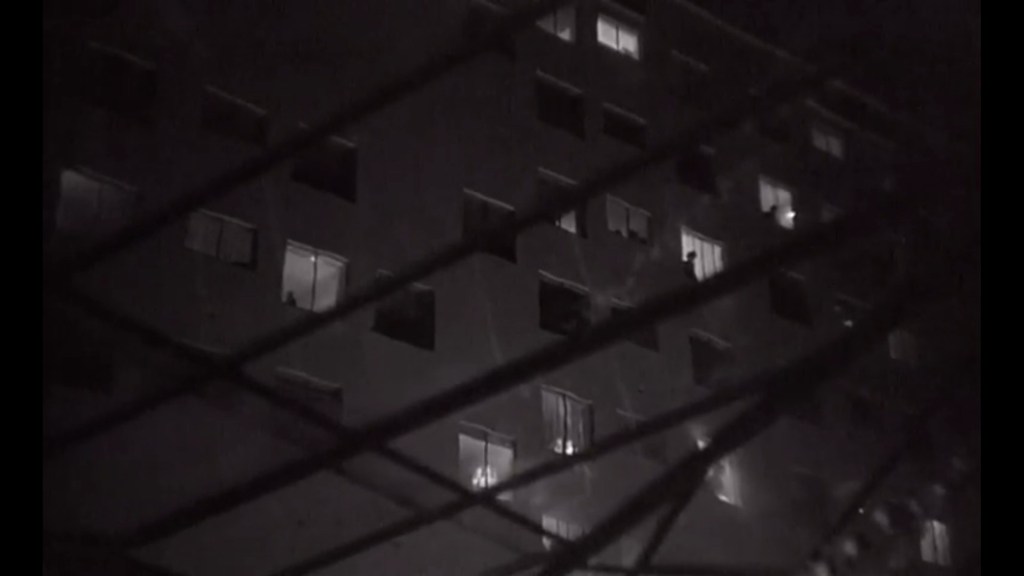

The underlying theme of this story is the tension between the rural or traditional past and the urban future of France, symbolised by the captain’s resistance to selling or giving up his pavilion in the middle of everything, which is always watched or seen by the neighbours. An individual facing massive housing construction and metropolitan expansion, in effect. The film points to the loss of identity and individual spaces, which is why it mentions the captain’s father and grandfather, but curiously, the director does not overdo the melodrama in this regard to sugarcoat or motivate the viewer to feel sorry for him. Real estate speculation and the imposition of modern urban models on everyday life were issues at the centre of the debate on urbanisation in France at that time, in the early 1960s.

The parts I enjoyed most were the captain’s interactions with the Andalusian and gypsy Spaniards in the neighbourhood, first playing with them and later offering his house for Pablo and María’s wedding. It was good while it lasted, as the tenants came to join the party and it all ended in chaos. I found the romance between the architect and Ania to be very contrived, and in any case, the old captain lost the fight against modernity and injustice, after even putting up with the shopkeepers refusing to sell him milk and other food on the way, and having to leave his home together with his fish César.

Leave a comment