If we knew how healthy our bad luck could be, we would have risked suffering it much earlier, voluntarily. The investigator in this story, Kyôhei Shibata, wasn’t even sure he wanted to be a detective, and he will succeed at the cost of discovering his bad luck. But that will remind him that in five years, glory awaits him, if his luck doesn’t change. The banality of the plot is counterbalanced, first of all, by extensive aspects of the story set in locations in Kobe, with ideal shots—Cinemascope-style framing—capturing spaces that six years later would cease to exist after being destroyed by the January 1995 earthquake, such as the Nagata Ward residential area and the Fukiai and Hyogo Ward commercial areas, (as the Letterboxed synopsis says);

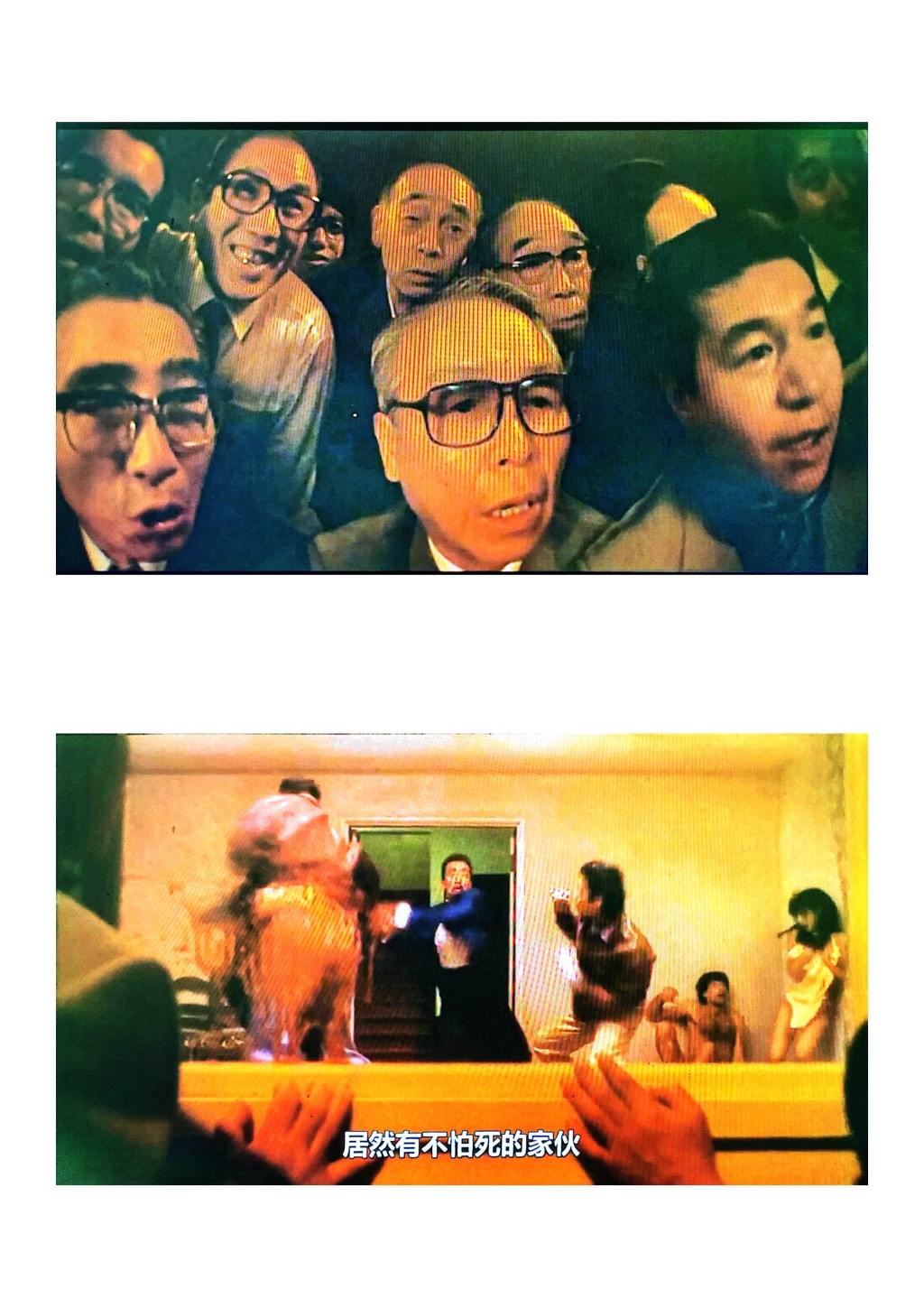

but also by the likeable but archetypal – because they are so slight – features of TV mini-series, the development and narrative rhythm of ‘Beppin Town’ is as if it were flowing somewhat tentatively, similar, incidentally, to the hesitant Shibata, a typical hard-boiled character who is an ‘amateur’ detective in this story. The professional indolence of the former law professor and prison boxer means that we cannot expect the film to escalate, either in terms of the beatings Shibata receives in the night district of Sannomiya, where underage girls are kidnapped for commercial orgies, or in terms of

the suicides (which turn out to be fake at the end) of the young Satomi Tamura and the boss Tomizawa

from the fifth floor, or the personal vendettas that started it all, or the question of whether to continue the investigation into the whereabouts of Machiko Nakajima, the rebellious daughter for whom he was hired. He got the job thanks to the beautiful Akiko. He meets Nakajima, who hires him at the Seaside Bar. Because he was an instructor at a detention centre before becoming a detective, and because he takes his time investigating, some viewers may think that his enthusiasm for the search is due to his inexperience, which is reinforced when he trains at a boxing gym and is later accompanied by Sayama, a former student, in his investigations.

A couple of guys, one of them quite funny with his knife, follow him closely until they have an altercation in an alley in the district, but nothing serious happens. He gets beaten up again when he is ambushed after having a Mexican Corona beer in the district where the disappearances are taking place. Although he returns with a bat and settles the score with both guys, they are smiling but toothless after being hit with a bottle and beaten up. Shibata has time to dismantle, together with Sayama, the residence where many young girls were taken to be raped while rich bourgeois pay the entrance fee and watch from behind a glass window. A fun Hollywood scene in the style of Charles Bronson breaking your head or, if you prefer, Belmondo half-killing everyone. His date with Akiko, for whom he seems to feel something deep, is interrupted just as he is walking with his camera towards Mount Rokko. When the supposed suicide of the boss Tomizawa occurs, Shibata assumes that revenge came from one of the two guys who were following him, who came from Yokohama to get hired by the boss and avenge the death of his exploited sister. Up to this point, the two guys following him were part of a Tosei clan, but it turns out that they will even help Shibata, giving him the address – Nadahama Town – where Machiko is staying with her lover Ryoji.

They escape by car, and here it looks like a scene from a Henri Verneuil film with the chase, and then almost in the underground. Finally, he fulfils his promise and returns Michiko to her parents, so this time he accepts the offer from the salesman and tailor Mr. Toh to buy a jacket and a tie. The ending, however, will not be this one. Sayama calls him when he is already dressed up for his date with Akiko and tells him that it has been determined that it was a young, beautiful woman with long hair who entered the hotel on the day of the boss’s death.

Akiko has taken revenge, getting ahead of her brother Ryoji to prevent his disgrace in prison. She turns herself in, obviously, and only at the end does the reviewer realise that the film’s score is like elevator music (with all due respect to the composers) because it is repetitive and bland, but at the very end it becomes clear that it was done this way so as not to create a saccharine effect in the truncated, or rather interrupted, romance between Shibata and the arrested Akiko, whom the amateur detective seems to swear he will wait for. Incidentally, in Kyotaro Nishimura’s short story “Shibata’s Good Deeds,” the author on whom the film is supposedly based, police officer Shibata – along with his partner Kosaka – engages in “good deeds,” which are nothing other than corruption. That is, Shibata commits petty theft from shops and stalls to frame homeless people or vagrants who will be unable to defend themselves.

Leave a comment