Moetsukita chizu rightly deserved an article in Cahiers du Cinéma (No. 206). Typical of Kobe Abe, through the dialogue and the indolence of the characters, the depersonalisation of post-war Japan is progressively amplified, to such an extent that it transcends the fictional context of the plot, almost to the point of cinema verité.Yoda Yoshikata, the writer behind Mizoguchi’s most important works, explains that Shintaro Katsu, who plays the detective in this film, was already the famous hero of the Zatôichi series when he met Teshigahara in a bar. Neither the director had ever seen an episode of Zatôichi, nor had the blind samurai seen any of Teshigahara’s films.

Zatôichi admitted to having read Kobe Abe and not understanding a thing, but that is exactly what adds spice to Moetsukita chizu: the director making his first feature film in Cinemascope and Katsu shunning the hero Zatôichi from 16 previous works.

In any case, we must begin by acknowledging that the detective’s investigation was doomed from the start. It cannot yield results or solve the mystery of Nemura’s disappearance, simply because, through the process of his inquiries, the perplexed anti-hero deconstructs what could be called ‘mystery’ in the face of an urban topography of diaphanous chaos but inherent in an undeniable collective nihilism. It could not be otherwise; if a country, after losing a war, privileges material and economic reparation, how could the values that are seen here as non-essential have a voice and a vote, or be given special consideration? Nemuro Hiroshi’s wife hires the detective, but who will provide the investigator with more support or information, even if unintentionally? The wife’s brother, a well-dressed histrionic man with high purchasing power thanks to his involvement in the illegal world of blackmail and business with women and others. Let’s put aside, which is not a minor issue, the generalised indolence everywhere – not to mention the indifferent behaviour of people in their daily lives – in the city where a cyclist crosses the road while driving, without caring if the detective runs him over, or a public works worker almost in the middle of the street works on a sluice or street tunnel without protection or warning a few centimetres from passing cars (00:57:13), and when he sees the detective in his car looking scared or annoyed, the worker even replies, ‘I don’t care if I die’. This is the moment when any viewer, not just the detective, would be justified in saying that they are confused.

The plot has long since changed course, from the confusion over the disappearance of a person whom everyone knew, and of whom no one has the same image or profile, to the confusion or mutual incompatibility of the people in the places frequented by the missing person. The message seems simple to see, but understanding it is another thing, and explaining it even less so: everyone knows each other, but no one knows each other. It’s like a David Lynch theatre of the absurd. The visibly angry detective does not hesitate to tell the wife, ‘You know nothing at all,’ when she tells him that she found her brother and that it was he who told her, and not her, the wife who in fact hired him for 30,000 yen a week, that Nemuro was not even well known at Dainen Fuel Company where he works. She does not seem concerned. In fact, when the detective asks her to concentrate on trying to remember details about her husband, anything would be helpful, he adds, she becomes agitated, ‘That’s impossible, impossible since he became a mystery after he ran away from here. Details like the way he whistled or wiped his nose or how he licked his lips when he smiled, they hardly feel like real images to me.’ It is clear that even for his wife, Nemura’s existential disappearance is almost immediate. oblivion rapidly devours in six months what people have lived through in an environment where emotional transience and almost complete lack of intimacy in the face of Western materialism abound (this would explain why the narrative begins with the date 2 February Showa 43, instead of 2 February 1968, using imperial eras rather than the Gregorian calendar as a foreshadowing of the contrast between tradition and modernity ).

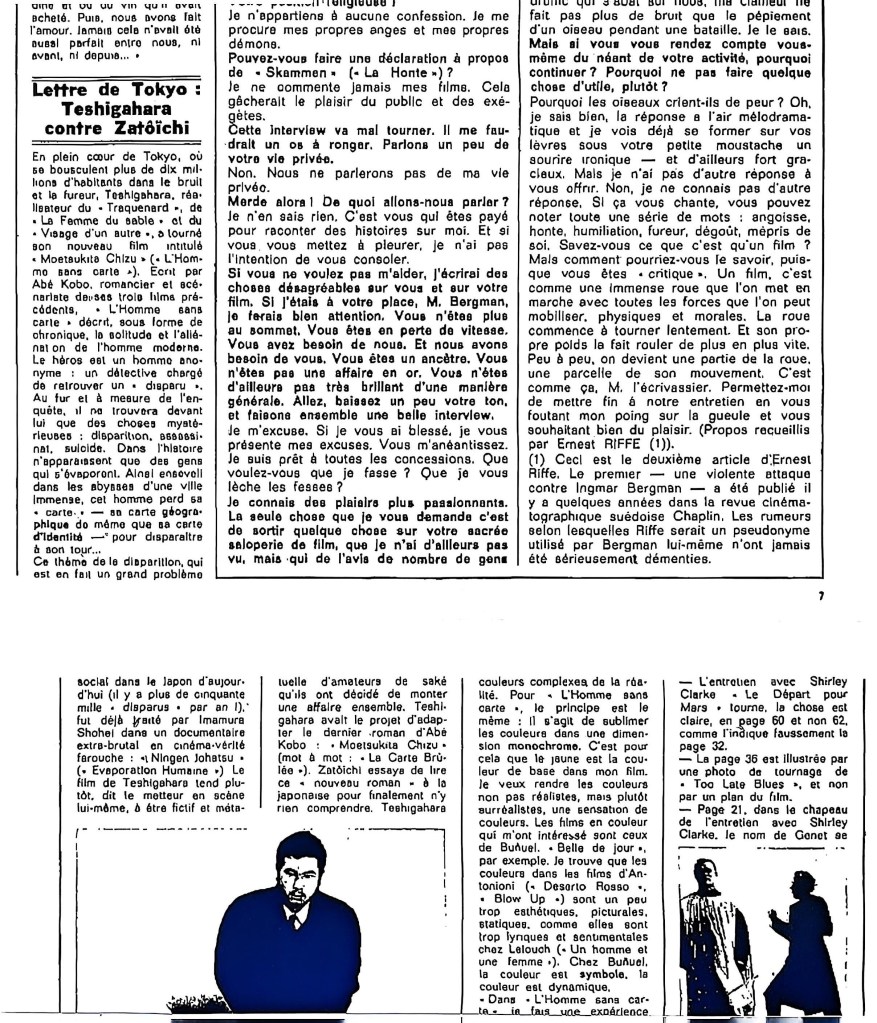

The detective is fired over the phone in the same Tsubaki café bar and clearly confesses to his wife in a later scene that no one seems to cooperate and everyone wants to know why he ran away or disappeared, but no one is interested in where he is at the moment. Y.K. is right, as Yoshikata wrote in Cahiers du Cinéma (isn’t it ironic or a luxury that Cahiers, in the midst of structural change, with a more political bent from around 1966 onwards, devoted space to Mizoguchi and now to Teshigahara?). Y.K. is right, I mean, when he observes that the least metaphysical of the heroes, Zaitochi, goes through a plot of profound alienation and social depersonalisation that merits an extra dose of existential metaphysics. The contradictions do not cease. The woman confesses that her husband earned 60,000 yen a month, but isn’t the detective paid 30,000 a week? Before dying in circumstances that are not revealed but would not have been surprising given his usual environment, the brother had expressed his desire to pay the detective the entire month’s fee to find his brother-in-law: 120,000 yen. In any case, the detective persists even though the agency he works for has fired him. When he returns to the Tsubaki café bar and asks a couple of the regulars there about the owner, who had already shown him hostility on previous visits, he is surrounded by another group of diners who beat up the former detective, forcing him to go to his wife for help, covered in blood. After he recovers, the desire returns, and the film’s climax could not be crowned with less irony than the wife, who could not show less concern for Nemura, becoming sexually involved with her former investigator.

When we witness at the end, that the detective has blended in, even if unintentionally, with the environment, then we understand not only that Toru Takemitsu's disturbing sound has supplied the dose that the story transmits, but that the scene of the vinyl, which the husband used to listen to - full of car sounds and not music, which he adored - that his wife played for the detective halfway through the film, was just one more sign, the type of cultural icons (musical obviously) that have been emptied of their pop meaning and turned into a password for this type of new citizens.

Leave a comment