Review by Fernando Figueroa.

Carrére deserves applause for risking upsetting those of us who read his novel. It is obvious that he preferred to appear to sabotage the order and final resolution of his work in order to take the canonical narrative thread of his text to postmodern paroxysm. First, there is Massimo Pupillo’s awesome original soundtrack, with distorted guitars emulating the contradictory anarchism of the Dionysian and Apollonian Limonov, interspersed with the band Shortparis. Then there is the balance of vintage aesthetics in the 16mm cinematography, which simultaneously shifts from 4:3 format in Moscow to 16:9 in the NYC sequences, which I had not seen used so efficiently since Jarmusch’s Paterson. Let’s start at the beginning. The first display of courage had to be faced by the author as the voiceover (I am referring to the novel) who devoutly narrates the Nietzschean personality of a fascist, pro-Stalin (‘if it weren’t for Stalin, you would all be speaking German now’) he replied to the panellists in the interview in Paris before smashing a glass bottle over one of their heads and emptying the water on the other) who also actively served the causes and war in Bosnia on behalf of ultra-right-wingers such as Karadžić. The key to his admiration for Limónov is revealed in the novel, in section 4 of ‘Paris, 1980-1989’ when Carrere tells him about the rude snub he received from the filmmaker Herzog. He was about to interview him and, beforehand, Carrere gave him a copy of his book to hear his point of view, to which the author of Fitzcarraldo replied when they came face to face, ‘Let’s not talk about that nonsense and get on with the interview.’ His friend said, ‘That will teach you to admire fascists.’

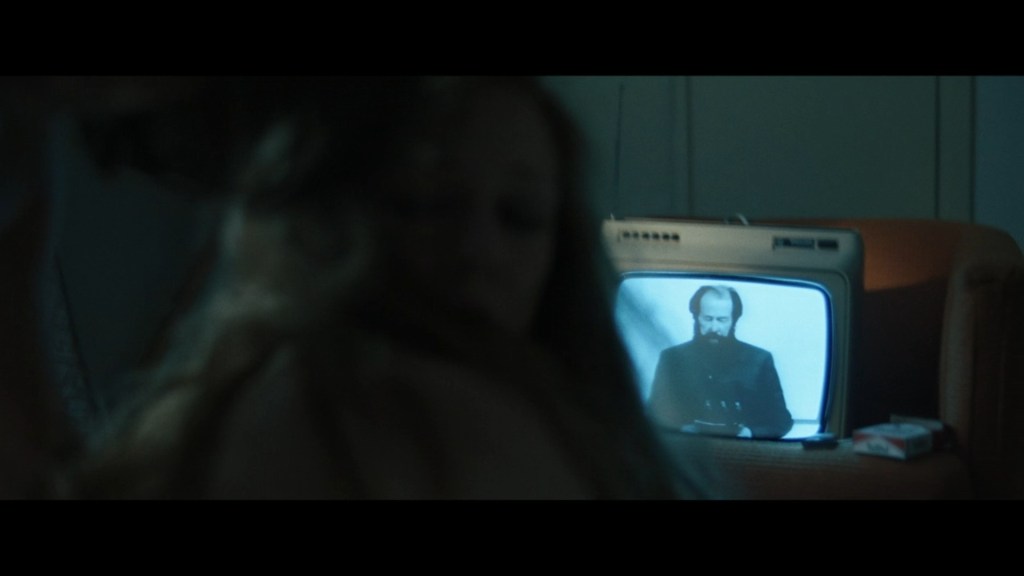

This film is disordered and, as I said above, requires the reader to have read the novel, as the film skips the order: Prologue, I. Ukraine, 1943-1967, II. Moscow, 1967-1974, III. New York, 1975-1980, IV. Paris, 1980-1989, V. Moscow, Kharkiv, December 1989, VI. Vukovar, Sarajevo, 1991-1992, VII. Moscow, Paris, Republic of Serbian Krajina, 1990-1993, VIII. Moscow, Altai, 1994-2001, IX. Lefortovo, Saratov, Engels, 2001-2003 and the Epilogue. Of the above, this film skips the entire prologue and (I) and more than half of (II). It focuses on (III) with flashbacks to (II) and returns to real time. Then, something that is incomprehensible from my point of view, it skips interesting anecdotes from (IV) and completely all of (VI), which is the part of Limonov’s activist life when he echoes, holding high-calibre weapons, in favour of the genocidal movement in Sarajevo, supporting the pseudo-Slavic cleansing of another of the men he admired besides Stalin, Karadžić. If Carrére aspired to vindicate Limónov’s contradictions, his time in Vukovar was essential, even if he had skipped his youthful arrests in chapter (I). Note that he did not skip the way he sodomises the beautiful Elena in the novel with all the anger that Solzhenitsyn on TV could have inspired in him. On the other hand, I would comment that the novel itself has its own level of disorder, although I admit that I enjoyed it. Its disorder consists of Carrére being the narrator talking about Eduard, but throughout the work, although mainly in some chapters with greater abundance, such as (IV) in Paris, Carrére digresses for at least 5,000 characters, and sometimes more, about his own life and autobiography until he returns to the thread of events happening to Eduard. In short, here in the film it starts in medias res and the chapters are edited asymmetrically in relation to the novel which, as I just mentioned, in itself opens up constant hyperbatons until it returns to the narrative thread. It is natural that this discourages an unaccustomed audience who, perhaps rightly so, do not want to play the calculator game for the biography of a fascist who adored other fascists and genocidal figures. Philosophically, Limonov seems to embrace a Nietzschean view of life as the will to power, where suffering and struggle are inevitable, but also the path to self-affirmation. His participation in conflicts such as those in the Balkans and his creation of the National Bolshevik Party can be interpreted as an attempt to overcome the ‘slave morality’ of his environment – both Soviet conformism and Western materialism – in order to impose his own worldview, however chaotic and contradictory it may be. However, his constant reinvention also reflects an existentialist struggle to define himself in an absurd world where there are no absolute truths or permanent homes. His time in prison in Lefórtovo and Engels, where he writes and earns the respect of his peers, can be seen as a moment of Sartrean authenticity, where, stripped of everything, he finds purpose in his resistance and his ability to inspire others. I have given it a 3-star rating because Whishaw’s performance is sublime, and because there is real craftsmanship, as I said, in the cinematography and the musical score, which I could only perceive as a paraphrase of the Velvet Underground. I have summarised the main parts of the novel.

These are notes from my reading that may be useful to those who are curious.I repeat, the following summary corresponds to the written work:

Prologue (Moscow, October 2006-September 2007) The prologue places us in Moscow after the shocking murder of Anna Politkovskaya on 7 October 2006, an event that shook the international perception of freedom of expression in Russia. The author, who was in the country at the time working on a documentary, is sent by a magazine to gather testimonies from those who knew the journalist. For a week, she visits the offices of Novaya Gazeta, where Politkovskaya was a prominent figure, as well as human rights associations and committees of mothers of soldiers killed in Chechnya. These offices, described as small and poorly equipped, reflect the fragility of the democratic opposition in Russia, a small circle of activists, often elderly, who represent almost the only resistance to Vladimir Putin’s regime. The author also interacts with French expatriates in Moscow, who express scepticism and disdain for the ideals of these activists, considering them irrelevant in a country more concerned with personal enrichment than with freedoms. Furthermore, the Western theory that Politkovskaya’s murder was ordered by the FSB or even by Putin is criticised, especially the idea that it happened ‘coincidentally’ on her birthday, which is ridiculed by a Russian-French friend, Pavel. This prologue not only establishes the political and social context of contemporary Russia, but also introduces the contrast between Western perceptions and Russian reality, setting the stage for the exploration of a life as complex and contradictory as that of Eduard Limonov, who will be the focus of the narrative. The text reflects a country where opposition is minimal and marginalised, and where accusations against the authorities are viewed with scepticism by some locals, while in the West they become symbols of repression. This initial scenario raises questions about the value of resistance in a hostile environment and the perception of truth in polarised political contexts, themes that will resonate throughout Limonov’s life and his personal struggle against power structures and social norms. The author also hints at her fascination with Limonov upon learning about his story, which motivates her to write this book as a means of understanding not only his life, but also the historical and social context of post-communist Russia and the impact of global events since the Second World War. This prologue, therefore, serves as a bridge between the present of 2006 and the past of Limonov, a man whose life seems to embody the contradictions of a country in constant transformation, between oppression and the search for identity, between rebellion and acceptance of an inevitable destiny. Ukraine, 1943-1967The first chapter covers the early years of Eduard Limonov’s life, born Eduard Savienko in 1943, against a backdrop of war and social transformation in Ukraine, specifically in Dzerzhinsk (formerly Rastiapino), an industrial city on the banks of the Volga River. His childhood is marked by the aftermath of the Second World War and the impact of the Stalinist dictatorship. His father, Veniamin, is a low-ranking officer in the NKVD, the precursor to the KGB, which gives the family a modest but privileged social status within the Soviet system. However, this position also generated tensions, as seen in the figure of Captain Levitin, a rival of his father who embodied injustice and humiliation in Eduard’s personal mythology, an idea he would later generalise by stating that in every person’s life there is a ‘Levitin’, someone who prospers unjustly at the expense of others. Stalin’s death in 1953, when Eduard is ten years old, is a defining moment; although he is a sensitive and obedient child, he weeps alongside his classmates for the loss of the leader, reflecting the indoctrination of the time and how historical events penetrate even the perception of children.

His childhood is also marked by heroic dreams inspired by his reading of Dumas and Verne, figures who fuel his imagination and his desire for an epic life, something that contrasts with the limitations imposed by his environment and his health, such as his short-sightedness, which prevents him from following in his father’s footsteps in a military career, which is a personal tragedy for him, as he has been brought up since childhood to despise civilian life and aspire to be an officer. As he grows up, his adolescence becomes more turbulent; he gets involved with street gangs in Kharkiv, participating in acts of violence, including a gang rape that leaves him emotionally confused and disgusted with himself. This episode, along with his first sexual experience with Sveta, an older girl who humiliates him by considering him immature, marks the beginning of an ambivalent relationship with women and power, where desire is mixed with frustration and violence. His life at this stage is defined by marginality, factory work and writing poems, which become a refuge for his growing discontent with Soviet life and family expectations. His admiration for Western cultural icons such as Alain Delon is also reflected, whom he imitates in an attempt to escape his own physical and social image, marked by insecurities such as his height and his need for glasses. His relationship with the KGB at this stage is rather comical, as seen in an episode where he helps a friend hide forbidden Western objects, showing a rebelliousness that is not yet political, but rather an instinctive reaction against the restrictions of his environment. This chapter portrays a young man caught between the expectations of an oppressive system and his own rebellious impulses, a theme that will recur throughout his life. His evolution from a sensitive child to a violent and disoriented teenager reflects the tensions of a Soviet society in transition after Stalin’s death, where the rigidity of the system clashes with the individual aspirations of a generation seeking its place in a world full of contradictions.

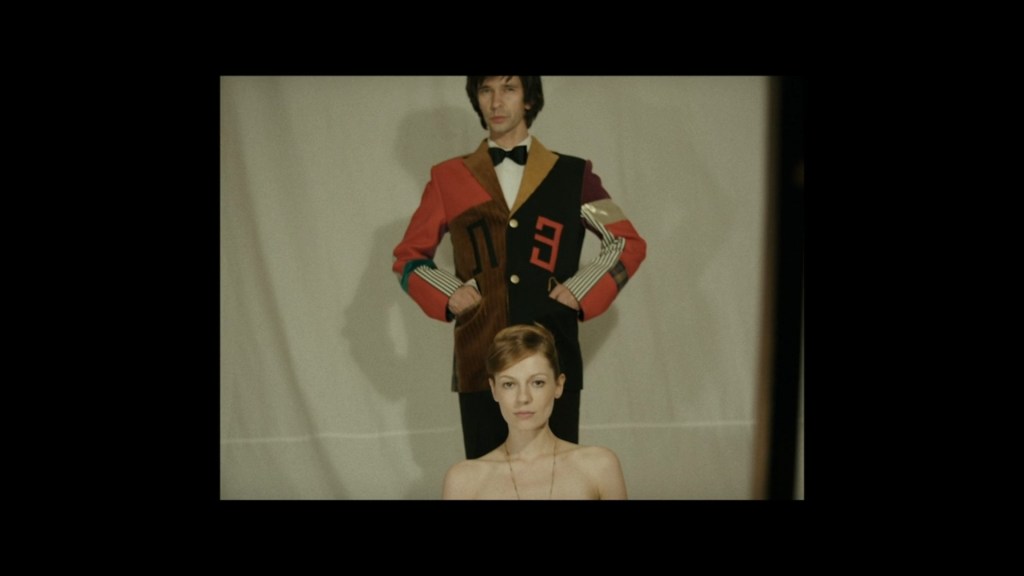

II. Moscow, 1967-1974 During this period, Eduard moved to Moscow, marking a significant change in his life as he entered the world of bohemian life and the Soviet underground during the period of stagnation under Brezhnev. In the late 1960s, he sought his own space as a poet and artist, distancing himself from his working-class and violent past in Kharkiv. Here he met Anna, an older woman with whom he had a complex relationship, and later Elena, a sophisticated young woman from the Moscow elite, who became the love of his life during this period. His relationship with Elena, whom he marries in a church and lives with in precarious conditions, elevates him to a position of prestige within the underground scene; together, they embody a kind of Soviet glamour amid the greyness of the Brezhnev era. The iconic image of Eduard in his ‘national hero jacket’ with Elena naked at his feet as they are photographed most likely symbolises personal triumph over the limitations of his humble origins. However, this period is also marked by emotional instability; his jealousy and obsessions, such as when he discovers Anna’s infidelity with an older painter, reveal a deep insecurity and a need for control in his personal relationships. His walks through the Novodevichy cemetery with Elena, where he mixes irreverence and passion, show his rejection of established cultural norms and his desire to assert himself as an outsider. In Moscow, Eduard also develops his identity as a poet, earning a place in dissident circles, although his life remains precarious, living in kommunalkas (communal flats) and facing the limitations of a repressive society. This period is crucial to his transformation from a rebellious young man with no direction to an artist aware of his potential to challenge the system, although his arrogance and need for validation lead him to personal conflicts and a life of excess. His relationship with Elena, though passionate, is tinged with social inequality and his own perception of being a ‘proletarian’ who conquers the ‘princess,’ a dynamic that empowers him but also hurts him as he is aware that he does not fully belong to her world. This chapter reflects Eduard’s internal struggle to define himself in an environment that represses individuality, as well as his growing ambition to transcend his humble origins through art and love, even though his insecurities and violent temperament remain an obstacle. The Moscow period also foreshadows his later exile, as his growing notoriety as a dissident puts him in the crosshairs of the Soviet authorities, paving the way for his departure from the country. In this sense, Moscow represents both a space of creative freedom and a reminder of the limitations of a regime that does not tolerate dissent, a theme that will mark his life in the coming decades.

III. New York, 1975-1980 This chapter is one of the most enjoyable for the narrative voice that speaks about Limponov, who is the spokesperson for Limónov’s own exploits. Not only because of its description of the two men’s limited English and their walks hand in hand in Greenwich Village, but also because of the contextual details, such as the references to Mexican Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz, the Bob Dylan vinyl with the Blowing in the Wind cover, and the interviews with Joseph Brodsky, which are dismissive or distancing in tone when compared to those with Jorge Luis Borges. After marrying Elena and meeting the Libermans, they send them a television so they can make faster progress in English. When they turn it on, lying in bed, Solzhenitsyn appears on screen, the sole guest on an exceptional talk show.

One of the best memories of Eduard’s life, says the narrator, Carrére, is sodomising Elena in front of the prophet who harangued the West and stigmatised its decadence. And so, while the voice of the author of The Gulag Archipelago can be heard on the television, it mixes with the moans of the slender Elena. In any case, in this city, Limonov undergoes a radical change as he confronts capitalist culture and individual freedom, which contrast sharply with Soviet oppression. During this period, he initially finds himself on the margins of society, working in precarious jobs and living in poverty, even as a beggar, before rising to roles such as valet for a Manhattan multimillionaire, reflecting his ability to adapt to extreme contexts and his constant personal reinvention. It was in New York that he began to write most prolifically, publishing works that combined his Soviet experience with his new life in the West, gaining some recognition in underground literary circles. This period was also marked by culture shock; Limonov, who had idealised the West as a place of freedom, was confronted with the alienation and materialism of American society, which made him feel ambivalent about the values he had initially admired. His life in New York was a mixture of fascination and disillusionment, for while he enjoyed the freedom to express himself, he also experienced loneliness and the struggle to survive in a city that offered him no stable place. This period was crucial to his development as a writer, as his experiences in the United States fuelled his provocative style and his critical view of both communism and capitalism. In addition, his time in New York allowed him to establish connections with other exiled intellectuals and artists, broadening his perspective on the world and himself. However, his rebellious nature and inability to fully adapt to social norms kept him in a state of outsider, a constant in his life that was accentuated at this stage by being far from his native country and any stable support network. Limonov also experiences a transformation in his perception of national and cultural identity, beginning to question what it means to be Russian in a global context, a reflection that will influence his future political and personal decisions. This stage ends with his departure for Paris in the late 1970s, seeking a new horizon where he can consolidate his literary career and find a sense of belonging that New York did not provide him. New York represents a period of self-discovery for Limónov, where the freedoms of the West mix with the difficulties of life in exile, shaping his identity as a writer and as a controversial figure who rejects both the Soviet system and the American dream.

IV. Paris, 1980-1989 In Paris during the 1980s, Limónov reached a peak in his writing career, becoming a fashionable figure in French literary circles. His interaction with figures such as Jean-Édern Hallier, a controversial editor and writer who welcomed him into his circle, offering him a space where his provocative style and Soviet past were valued as exotic and transgressive, is mentioned. During this period, Limónov published some of his best-known works, such as Portrait of a Teenage Bandit, The History of a Scoundrel, and The Great Era, about his years in Kharkiv. In all of these works, he combined autobiography with fiction to recount his life in exile, earning both admirers and critics for his raw tone and rejection of literary and social conventions. Paris offered him an intellectually stimulating environment where he could explore themes of sexuality, politics and marginality without the restrictions he faced in the Soviet Union or the extreme economic difficulties of New York. However, his personal life remained turbulent; his relationship with Natasha, who accompanied him during this period, reflected a dynamic of dependence and conflict, especially due to her alcoholism, which saw her returning home dishevelled at dawn, while his friendship with Jean-Édern Hallier, who was experiencing financial and legal difficulties, highlighted the precariousness of his social position, even in a place where he was recognised. Quite apart from this is the incident in Budapest with the Robbe-Grillet family and other writers, where Limonov publicly stated that he detested the proletariat because he had been personally poor and hated poverty. It all ended in a fistfight. A significant episode is his visit to Hallier’s castle in Brittany, where he experiences a mixture of admiration and sadness at his friend’s decline, as well as a reaffirmation of his own ambition to transcend his environment, as when he declares that he is preparing to ‘take power’ in Russia. Paris also represents for Limonov a space where he can reflect on his identity as a Russian in exile, and his growing discontent with life in the West leads him to reconsider his relationship with his native country, laying the groundwork for his eventual return.

This stage is crucial for his consolidation as an international writer, but also for the development of his political thinking, which begins to shift towards nationalism and a rejection of both Western liberalism and Soviet communism. Limonov finds himself in a constant tug-of-war between literary success and personal alienation, reflecting his inability to find a true home, whether in geographical or emotional terms. His time in Paris, therefore, is a period of recognition and creativity, but also of growing unease and preparation for a return to Russia that will radically change his trajectory. In this city, Limonov experiences the height of his literary fame, but also the emptiness of living disconnected from his roots, which pushes him towards a search for meaning beyond literature, in the political and social sphere, marking a turning point in his life that will take him back to a country in transformation at the end of the 1980s.

V. Moscow, Kharkiv, December 1989 Limonov’s return to Russia in late 1989 coincides with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the beginning of a period of chaos and transformation in the country. His return to Moscow and Kharkiv is motivated by a desire to reconnect with his roots and participate in the historical events that are redefining Russian identity. In this context, Limonov finds a Russia very different from the one he left in the 1970s; the Soviet system is crumbling, and new opportunities and challenges are emerging in an atmosphere of economic and political uncertainty. His life during this period is marked by the search for a new role in a society in transition; he is no longer just the dissident poet or exiled writer, but begins to position himself as a public figure with political ambitions. It is likely that at this stage he began to interact with nationalist and marginalised groups, laying the foundations for the creation of the National Bolshevik Party (Nasbols), which he would found a few years later. His return also meant a confrontation with his personal past; visiting Kharkiv, his hometown, probably brought back memories of his turbulent childhood and adolescence, reinforcing his desire to redeem himself or impose his vision of what Russia should be. This chapter is brief but crucial, as it represents Limonov’s transition from an artist in exile to a political activist in his native country at a time when Russian history is at a turning point. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the opening up to capitalism generate in him a mixture of fascination and rejection, as he sees both corruption and emerging inequality as an opportunity to influence the future of the country. In Moscow, Limonov also faces the material realities of post-Soviet life; unlike the abundance of certain luxury goods, basic necessities are hard to come by, as reflected in his consumption of simple products such as broth and homemade chocolate. This return to Russia is therefore a time of introspection and personal redefinition, where Limonov begins to channel his rebelliousness and desire for transcendence into the political arena, gradually abandoning his identity as a writer to become a charismatic leader of a radical movement. This chapter also foreshadows the conflicts he will face in the 1990s, both with the government and with other political groups, as he seeks a place in a fragmented and chaotic Russia, where old structures have collapsed and new ones have yet to take hold. His experience during this period reflects the tensions of a nation in crisis, as well as his own internal struggle to find a purpose beyond art, in a context where politics becomes the new battleground for his ideals and frustrations accumulated over decades of exile and marginalisation.

VI. Vukovar, Sarajevo, 1991-1992Limónov becomes involved in the conflicts in the Balkans, specifically in Vukovar and Sarajevo, during the most intense years of the war in the former Yugoslavia. Limónov acts as a ‘lost soldier’ in this region, suggesting active participation in the conflict, probably aligned with Serbian forces, given his subsequent involvement with the Serbian Republic of Krajina. This stage reflects his transformation from an intellectual to a man of action, seeking in war a form of personal and political transcendence that he did not find in literature or in life in exile. His involvement in the Balkans is controversial; Limónov not only observes the conflict but becomes directly involved, adopting a nationalist stance that leads him to support the Serbs in their struggle against what he perceives as the oppression of Western forces and the policies of disintegration of Yugoslavia. This decision alienated many of his former admirers in the West, who saw his support for the Serbian militias as a betrayal of democratic and humanitarian values. However, for Limonov, this war represented a struggle for identity and sovereignty, ideals that he projected from his own experience as a Russian in a post-Soviet world where Western influence seemed to dominate. His time in Vukovar and Sarajevo also highlights his fascination with heroism and violence, recurring themes in his life since his adolescence in Kharkiv, but now elevated to a political and ideological level. In this context, Limonov experiences first-hand the brutality of war, which probably reinforces his view of life as a constant struggle where only the strong survive. This stage is crucial to his political radicalisation; his experiences in the Balkans consolidate his rejection of the Western-led international order and his belief in the need for armed resistance against what he considers cultural and political hegemony. Furthermore, his participation in the conflict gives him a certain aura of martyrdom and warrior among his followers in Russia, although it also makes him a polarising figure both inside and outside his country. This chapter therefore marks a point of no return in his career, where he abandons any pretence of neutrality or mere intellectual provocation to actively commit himself to causes that combine nationalism, anti-imperialism and a romantic vision of armed struggle. His time in the Balkans also reflects a deep loneliness and a search for belonging; by joining a foreign conflict, Limonov attempts to find a purpose that transcends his own personal history, but at the cost of his reputation and his connection to many of his former allies. This period reflects his constant need to reinvent himself, even if it means embracing chaos and violence as means to achieve an ideal that may ultimately be unattainable.

VII. Moscow, Paris, Serbian Republic of Krajina, 1990-1993He divides his time between Moscow, Paris, and the Serbian Republic of Krajina, a self-proclaimed territory during the war in the former Yugoslavia. In Moscow in 1993, Limonov witnesses key events in the post-Soviet political crisis, such as Yeltsin’s dissolution of the Duma, a moment of extreme tension that reflects the chaos of Russia at the time and likely reinforces his desire to influence the country’s future through political action. In Paris, his connection with figures such as Jean-Édern Hallier remains an anchor, although this relationship is marked by Hallier’s decline, both economic and personal, reflecting the fragility of Limonov’s support networks in exile. His involvement in the Serbian Republic of Krajina indicates a continuation of his involvement in the Balkans, where he supports Serbian forces in their fight against Croatia and Western interventions, consolidating his image as a defender of nationalism and a fierce critic of NATO and the United States. This period is crucial for the founding of the National Bolshevik Party (Nasbols), a movement that combines elements of Russian nationalism with anti-capitalist and anti-Western rhetoric, reflecting the contradictions of his political thinking, which mixes nostalgia for certain aspects of the Soviet past with a rejection of global liberalism. In Moscow, Limonov also faces the difficulties of everyday life in a Russia in economic crisis; his consumption of staple foods such as broth and homemade chocolate contrasts with the abundance of luxury goods available to the ‘new Russians,’ showing his alienation from the emerging elites and his identification with the marginalised. His time in the Krajina positions him as a charismatic leader for some and a scoundrel for others, a dualism that he himself recognises and that the author of the text leaves open, reserving a definitive opinion on his morality. This chapter reflects Limonov’s consolidation as a political figure, gradually abandoning his identity as a writer to focus on direct action and the construction of a movement that, although marginal, has a significant impact on certain sectors of Russian society dissatisfied with the post-Soviet transition. His life during this period is a constant journey between opposing worlds—Parisian sophistication, Moscow chaos, and the brutality of war in the Balkans—symbolising his inability to find a stable place in the world, as well as his desire to transcend through struggle and leadership. This chapter also shows his growing radicalisation, which leads him to confront both the Russian government and international powers, positioning him as an outsider on all fronts. Ultimately, this stage reflects his search for a heroic ideal, often at the expense of his own humanity and his connection to those around him.

VIII. Moscow, Altai, 1994-2001During this stage, Limonov establishes himself as the leader of the National Bolshevik Party, consolidating his role as a political figure in Russia, while dividing his time between Moscow and the Altai Mountains, where he trains and lives with his followers, the Nasbols. This period, which spans the turn of the century, is marked by his growing opposition to the Putin regime and his attempt to build a movement that combines elements of nationalism, socialism, and armed resistance. In Altai, Limonov and his followers live in austere conditions, adopting an almost monastic lifestyle that reflects his ideal of a soldier-revolutionary; descriptions of evenings with his young followers, roasting shashliks and sharing wine, show a more human and tender side to Limonov, who feels like a father to these young idealists. However, this phase ends abruptly with an FSB raid on their camp in Altai, where he and his nasbols are arrested by special forces in an operation that mixes violence with moments of absurd cordiality, such as when a soldier confesses his admiration for his books or when Colonel Kuznetsov shares vodka with him during the transfer to Gorno-Altaisk. This episode reflects the constant tension between his role as a subversive leader and state repression, as well as the ambiguity of his relationship with the authorities, who oscillate between respect for him and the need to neutralise his influence. In Moscow during this period, Limonov also faces the reality of a Russia increasingly controlled by Putin, which intensifies his anti-establishment rhetoric and his commitment to resistance. His life in Altai, on the other hand, symbolises an attempt to escape corrupt modernity and build a community based on values of camaraderie and struggle, although this utopia is constantly threatened by political reality. This chapter also shows his growing fascination with mystical experiences, such as when he interprets an encounter with ‘celestial music’ as a sign of his destiny, either as a leader of Eurasia or as a martyr. His arrest in 2001 marks the beginning of a new chapter of imprisonment, but also reinforces his image as a tireless fighter against the system. At this stage, Limonov seems to find purpose in his role as leader of the Nasbols, although he remains an isolated figure, unable to fully connect with broader Russian society. This period reflects his constant search for transcendence, whether through politics, violence or spirituality, in a context where his every action is seen as a threat by the state. Ultimately, his life in Moscow and Altai during these years is a testament to his resilience and ability to inspire others, but also to the loneliness and frustration of fighting against a system that seems invincible.

IX. Lefórtovo, Saratov, Engels, 2001-2003The last chapter detailed in the texts covers Limonov’s period of imprisonment following his arrest in Altai in 2001. He is transferred to several prisons, including Lefortovo in Moscow, and then to camps in Saratov and Engels, the latter known as ‘Eurogulag’ for its modern and supposedly model design, although Limonov finds it just as oppressive as traditional camps.

During his time in prison, which lasted until 2003, Limonov not only survives the harsh conditions but also earns the respect of prisoners and guards alike, being seen as a leader and almost a saint for his ability to help his fellow inmates. He writes several books during his imprisonment, demonstrating his resilience and commitment to intellectual creation even in the worst circumstances. A revealing anecdote is his comparison between the minimalist design of Engels’ toilets and those of a luxury hotel in New York designed by Philippe Starck, reflecting the breadth of his experiences and his ability to find parallels between such disparate worlds. This stage of his life is a high point in his image as a man who has lived at opposite extremes – from the glamour of exile to the suffering of the gulag – and he himself is proud of this uniqueness. His time in prison also reinforces his image as a martyr among his followers, consolidating his status as a symbol of resistance against Putin’s regime. However, this period is also a time of personal reflection; Limonov seems to accept his fate with a mixture of stoicism and defiance, responding ‘normalno’ (everything’s fine) when asked about his experience in prison, although he later reveals details that show the emotional weight of his imprisonment. His release in 2003 is a moment of symbolic triumph, as even the guards and prisoners compete to help him with his luggage, reflecting the charisma and authority he wields even in such a hostile environment. This chapter represents not only a period of suffering, but also a reaffirmation of his identity as a tragic hero, someone who has faced state repression and emerged stronger, at least in spirit. His prison experience also seems to deepen his contempt for power structures, both in Russia and around the world, and his determination to keep fighting, although his approach may have changed after this period of forced introspection. Ultimately, this stage reflects his ability to transform suffering into a narrative of resistance and heroism, a constant in his life that allows him to maintain his relevance as a political and cultural figure, even in the face of the most extreme adversity. His time in prison is, therefore, a testament to his resilience and his inability to be completely silenced, a theme that resonates with his life’s journey of struggle and reinvention.

Epilogue: This serves as a reflection on Limonov’s life after his release in 2003 and up to the narrative present of the book (around 2006-2007, coinciding with the prologue). In this period, Limonov continues his struggle as leader of the National Bolshevik Party, facing increasing repression under Putin’s regime, which consolidates its power in Russia. The epilogue is likely to explore how his figure remains polarising; for some, he is a hero who defends the marginalised and challenges oppression, while for others he is a dangerous extremist whose ideas and actions threaten the stability of the country. His post-Soviet life is marked by constant tension with the authorities, including further arrests and restrictions on his political movement, reflecting the difficulty of maintaining a radical opposition in an increasingly authoritarian Russia. On a personal level, the epilogue could address his ageing and his reflections on a life full of extremes, from the poverty and violence of his childhood to literary recognition in exile and his transformation into a political leader in his native country. His inability to find peace or a permanent home, a constant theme throughout his life, is likely to be highlighted, as is his persistent desire to leave a mark on history, whether through literature or politics. This final chapter could also connect with the context of the prologue, drawing parallels between his struggle and that of figures such as Anna Politkovskaya, whose murder symbolises the dangers of challenging power in Russia. The epilogue, therefore, would be a synthesis of his life as a journey of rebellion, suffering and the search for transcendence, reflecting not only his personal history, but also that of Russia from the Second World War to the present day, a country which, like Limónov, has oscillated between greatness and chaos, between oppression and the search for identity. His legacy, ambiguous and controversial, would be presented as a reflection of the contradictions of his time, leaving the reader with open questions about the value of his struggle and the impact of his life on a world that continues to face the same dilemmas of power, freedom and resistance. Ultimately, the epilogue would serve as a melancholic but defiant conclusion, showing a man who, despite everything, refuses to give up, even if his struggle seems increasingly lonely and misunderstood.

Leave a comment