Review by Fernando Figueroa

A filmmaker rushed to film himself on Super 8 while he slept in order to fuel his creativity, and the echo of sleepwalking and vampirism he had in mind during the process barely allowed him to realise that it is not actually him controlling the camera, but rather a simple character in the script by Zulueta, the director of Arrebato. Zulueta lives in precarious conditions in post-Franco Spain, but post-Franco did not mean post-censorship, so he revisits the ideas of the ill-fated short film that never saw the light of day and, like the other morally incendiary militants of the Madrid scene, such as Pedro Almodóvar, he took advantage of the slight respite in Spain in the late 1970s – even with the rise of ETA – to leave us this experimental cinematic artefact in which, through a tortuous self-referentiality, the creative vampire is rather the object created and, more precisely, consumed by the camera, as we see in the emaciated Pedro.

Zulueta sympathised with the DIY counterculture movement, which attacked all the comforts and material expressions of the prevailing capitalism, so it is no surprise that heroin addiction plays a role in the metaphor of this story, acting as a two-sided mirror, as it fuels the creative bonfire with the wind that stirs up the beta-endorphins, but on the other side it sucks out all the magma from the filmmaker, who, from the enthusiastic beginning of the journey, suddenly finds himself on a trip to the dark abyss of inspiration at the cost of energy, of life… I was going to say at the cost of money, but such subtleties are marginal in the lysergic flight that carries the narrative thread. For example, Pedro has no choice but to continue until the orgasm of that vampiric discovery, and even so, we should ask ourselves when he buys his rolls of film, how does he pay for them? Who supports him? I mean, the shopkeeper charges him 4,000 pesetas, which in those days, let’s say 1978, was 70 pesetas to the dollar, and with today’s inflation, 4,000 pesetas would be no less than $250 for a simple purchase to feed his vice, every four days?

Beyond any interpretation of a camera as a devouring entity, there is no denying the feverish paranoia that will consume the exhausted José Sirgado. This symptom must be seen as inherent to a Spain plagued by low wages and a lack of cultural variety. José abuses heroin, and from here, any viewer can expect anything. Is his paranoia inflicted by his drug use and therefore obedient to his addiction? Or is there something else?

The beginning of the story shows us him exhausted in the film, and perhaps in vain. He arrives at his flat and his lover Ana has returned, and suddenly he discovers that a package has arrived for him. It is a tape recording by Pedro, Marta’s young cousin, whom she met one hot day, and the reason for the letter is a flashback to her encounter with the eccentric young man and his camera and the unexpected way in which her curiosity was aroused by that trip to the countryside, as she recalls. Some time later, she returns with Ana, who is sceptical about the boy but nevertheless accepts Pedro’s challenge of spending two hours in front of the TV.

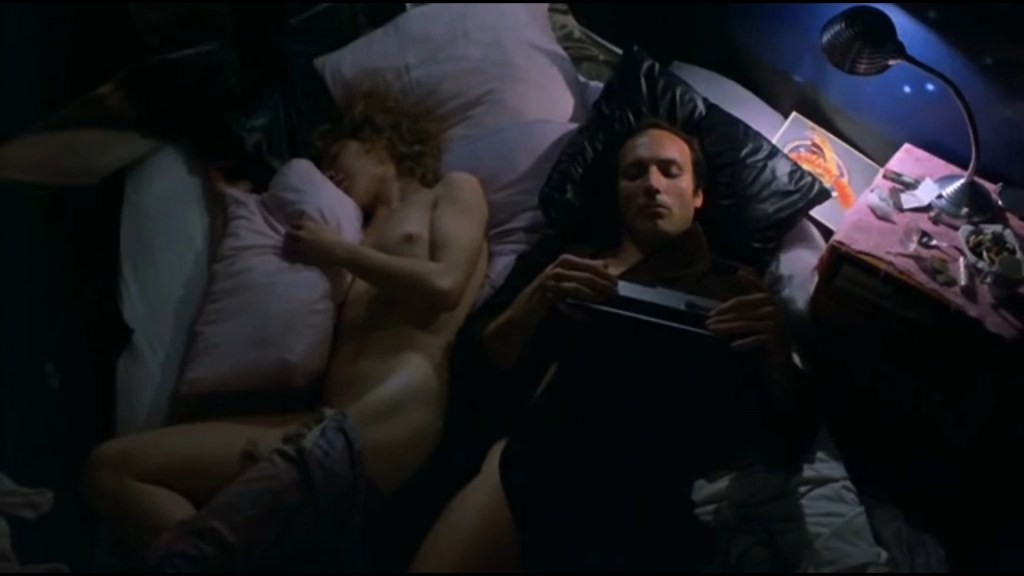

The socio-economic criticism has already been alluded to, and now with the Betty Boop doll, it could be seen as a kind of psychoanalytic regression or at least an identity crisis for Ana, but only a few minutes are devoted to it, and given that she also shares an addiction to the occasional line of heroin, it again detracts from the message or interpretation that can be made of the toy. In any case, as time passes, the film’s narrator, that is, Pedro’s voice in the letter about his creativity, combines suspense with the experimentation he carries out while filming and getting involved with many people in order to continue his aesthetic and existential trials until he begins to notice certain images with a red hue or streak in the developed rolls of film. By then, the relationship between him, José and Ana is no longer conducive to further creativity. She even suggests making another film together, but José has been affected by his tape recorder’s influence, displaying the same pathological behaviour (whatever that may be) and no longer interested in sex or drugs, much to the intrigue of Pedro, who every four days develops his films, which he shoots incessantly while he sleeps and in which the red streak gradually absorbs the film. He calls this pleasure or lust for seeing or feeling himself between the lens and himself ‘outbursts’.

Counting them, Pedro realises that, counting the strips, he only has two more ‘outbursts’ left before there is no trace left on the film, and that is when the story returns to the beginning, because that is where the reading of what has been received ends. Pedro asks him to go and get the last tapes. José cannot find him at that address. He waits four days for the film to be developed and when he plays it back on the projector, he realises that Pedro is him, José, as the images are projected. Any interpretation would be purely metaphorical, which I will reserve for myself, simply to point out that the film achieves a natural conceptual and dreamlike euphoria that lends itself to over-interpretation, including the nuances of political rebellion that it seems to be meta-narratively addressing.

Tag: Post-Franco Spanish Cinema Movida Madrileña

Leave a comment